Join smart, curious folks to get the Data Ops 📊 newsletter each week (it’s free!)

What can you do with a spreadsheet?

Yes, I’m talking about Excel, Google Sheets, and all of the other Software as a service tools that let you put numbers and formulas into a grid. Because the logic is expressed in a model allowing you to plug in your own data, it’s an easy way to share a functional solution to a problem.

Why use a spreadsheet? To some, it is a simple calculator. To others, it is a way to create financial models or other decisions. Spreadsheets have lots of limitations. It’s very hard to use for people who don’t know spreadsheets. It’s even harder to use spreadsheets as a multiplayer game.

In the hands of Tyler Robertson, spreadsheets are a programming canvas. Here are a few examples he’s built without resorting to external programming:

docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d…

Tyler Robinson’s Google Sheets suggest a future where Spreadsheets behave more like deployable applications. The “grid” of rows and columns is a low-resolution vision of what’s possible.

Why Use Spreadsheets?

Spreadsheets let you express logic on a canvas. Because the information is displayed on a grid, we tend to think of it as bound to x and y dimensions. But perhaps we should be thinking of spreadsheets as the predecessors to a new kind of functional programming.

For example:

Excel supports 1,048,576 rows by 16,384 columns (about 17 million cells)

Google Sheets? Up to 5 million cells for spreadsheets that are created in or converted to Google Sheets with 40,000 new rows at a time, and a maximum of 18,278 columns

Spreadsheets, if you consider them analogous to digital cameras, have hit an information level of 17m items. This is a lot of information, and most people don’t come close to exercising the format to its limits like Tyler does in the tweet above.

But where could they go? The human eye has a theoretical limit of 576 megapixels – meaning that even at current limits it’s probably 10-20x as sharp as the best digital photos. Our current information resolution in spreadsheets is like an 8-bit video game. If you zoom out things look pretty cool but when you focus they are pretty chunky.

If the brain is an analog to a spreadsheet, we’ve got a long way to go before we can store the depth of information (number of rows), the complexity of model (intelligence?), and the speed of recall (search).

Functional Programming in a Spreadsheet

We don’t need to invent a whole new model to improve spreadsheets along these dimensions. We do need to improve spreadsheets in areas where they have low information resolution.

What would this look like?

A better spreadsheet might:

-

store and retrieve many more rows (like a database)

-

search in flexible ways (like a graph database or a highly tuned index like Elastic or Algolia)

-

provide suggestions for next actions based on the schema, structure, and model of the spreadsheet (exploring “what if” scenarios based on a known structure)

All of these improvements seem straightforward. You want to avoid having a practical limit to rows, unless you are storing some unimaginably large set of data. You also want to create a way to search and filter for information that lets multiple people use a spreadsheet model without breaking each other’s logic. And you want to provide “intelligent” next action suggestions based on what the user is doing.

But implementing any one of them is fraught with peril.

What is a “large” number of rows? How do you let multiple people use a model without breaking it and also without prescribing the way that they do things? Who knows when intelligent next actions deliver any real value?

Even a smarter spreadsheet with many fewer limits requires the right logic, placed in the right sequence, and a user experience that makes it easy for the user to complete the job they tried to do.

AI will not save the day

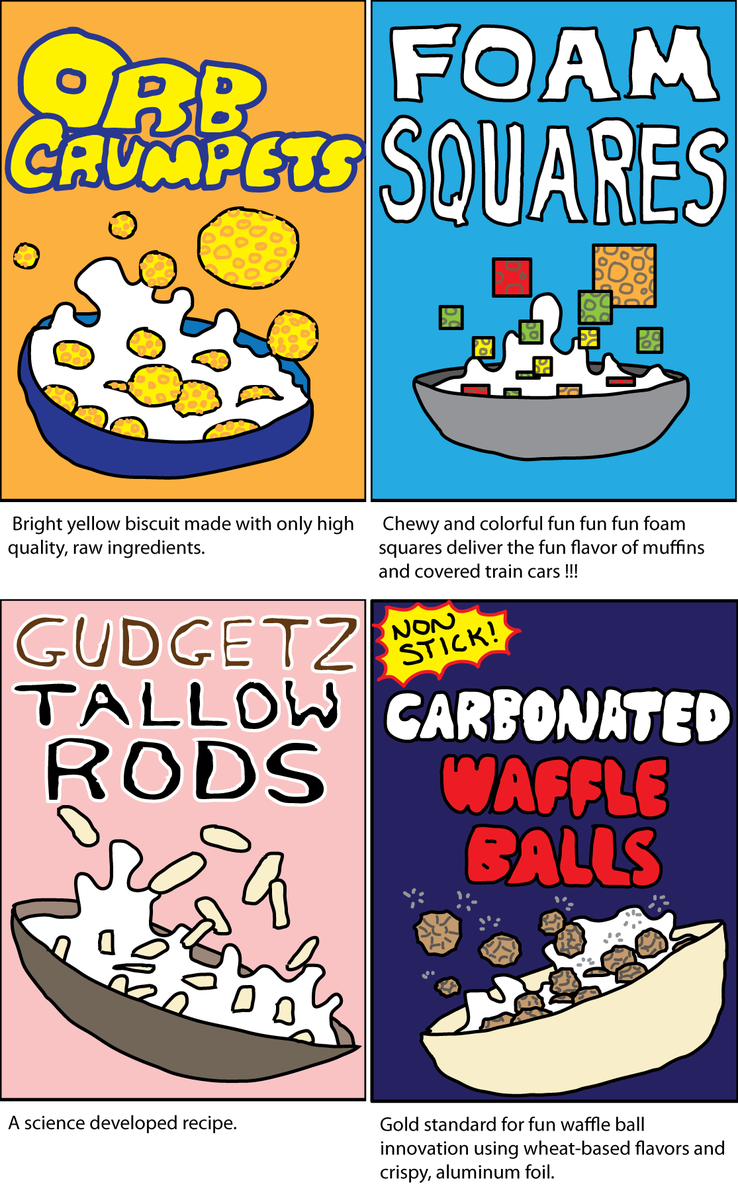

Pointing an AI model at many many spreadsheets probably won’t give you the right answers, either. Here’s a humorous example that Janelle Shane created with GPT-3 where she asked it to make new breakfast cereals from existing examples. One can only imagine the weird spreadsheets GPT-3 might make out of spreadsheet templates.

The cereals from Ada, the smallest GPT-3 model, were a bit questionable.

aiweirdness.com/new-breakfast-…

Machine learning is not an inherently bad idea. But it needs to be focused on small changes across many observations to deliver solid results.

A new way to spreadsheet

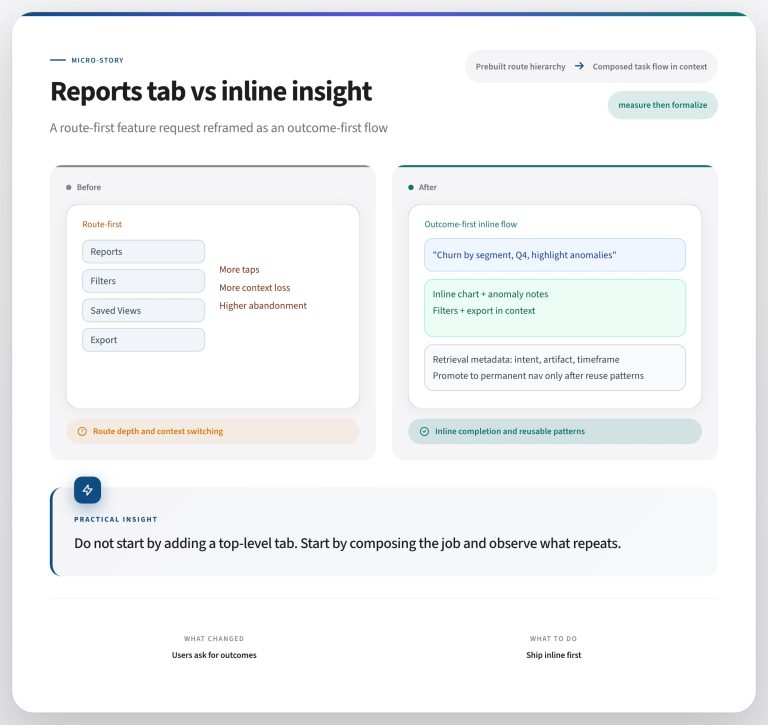

Tyler Robertson’s spreadsheets suggest a new way to build decision models in Spreadsheets that looks more like functional programming.

Spreadsheets need reusable building blocks. These would work like pluggable models that define their own logic and work independently.

What if …

-

you could compose a spreadsheet model from other functions?

-

in doing so you could identify the Inputs needed to run that model and automatically connect them to the corresponding values in your current spreadsheets

-

and then connect that model in turn to another?

This would give you the basic model that we use today in spreadsheets – a row-based way to manipulate numbers with formula functions – and a more flexible, pluggable model to add logic that helps with particular problems.

“Functions” then are run within individual spreadsheet modules, taking as input the output from other modules, and delivering the results down the line.

The application (because functionally, this is an application) is able to do much more than a simple spreadsheet model. And it retains the basic abilities of a spreadsheet.

What’s the takeaway? Spreadsheets are logical building blocks to assemble into applications that run in context of the data you provide. Most of the time we think of these things as disconnected and starting to think of them as logical data pipelines provides a lot more flexibility, power, and utility.

A Thread from This Week

A Twitter thread to dive into a topic

Calls would be easier to screen with context (people sometimes text for permission to call). What if there were a feature for this?