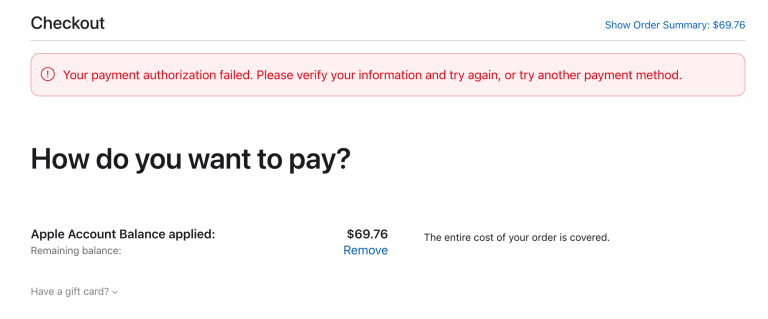

Who owns the customer experience, really? When a problem happens, we typically point at the team that owns that feature in the product. But most ownership problems aren’t caused by unclear roles or missing accountability. They happen because no org chart maps cleanly to how customers actually experience a product.

Features, reliability, support, and recovery live in different teams, but the customer experiences them as a single, continuous journey. The customer doesn’t care if a problem happens due to team 1’s feature or team 2’s feature. They just know they have a problem. When teams focus on optimzing their slice of the system, no single owner can see, let alone fix, the full impact.

This is why ownership debates feel endless and unsatisfying. Everyone is partially right. Everyone is locally correct. And the customer still has a broken experience.

The ownership problem is structural, not managerial

Organizations often respond to fragmented ownership by tightening control. They assign a DRI. They escalate decisions to leadership. These moves concentrate accountability, but they don’t change how decisions are made in the moment. They treat ownership as a reporting problem instead of a systems problem.

The systems problem is that the org divides responsibility along internal boundaries, while the impact is felt end-to-end. A product team can ship a feature that works by design and is very different than a similar feature created by another team. A platform team can keep systems healthy without observability metrics that detail customer pain. The support can resolve tickets within a service level agreemnt while still disappointing the customer.

And the customer can still lose trust because the experience no longer makes sense from one step to the next.

Customer journey ownership fails when responsibility is evaluated locally and is disconnected from the global experience.

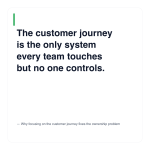

The customer journey is the only end-to-end system

No one team owns the entire customer journey. That path starts before the customer is ready to buy, continues through mid- and bottom- funnel actions, and begins again in an activation journey as a customer. When the back-end organization changes, the customer journey rarely changes along with it.

That makes the customer journey the only system that:

-

every team touches,

-

no team fully controls, and

-

cannot be optimized locally without visible consequences.

Focusing on the customer journey fixes the problem from the outside in. You don’t need to re-org the team to create a shared reference teams can use even when they have fragmented responsibility.

When the customer has a problem and teams disagree about what to do, the customer journey delivers a more useful question than “who owns this?”:

Does this preserve the customer’s ability to predict what happens next?

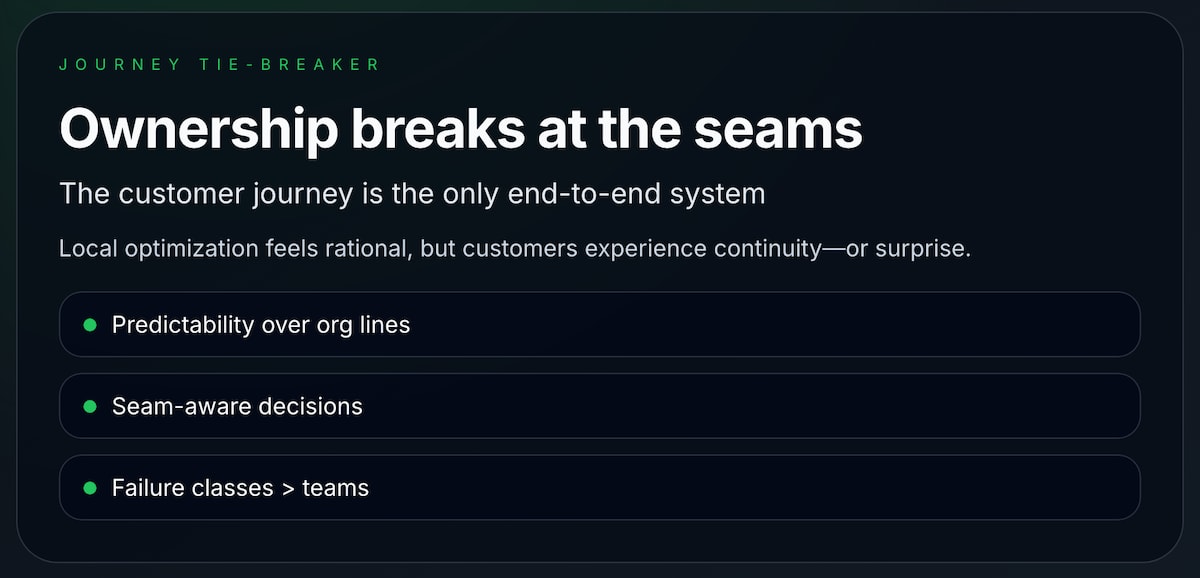

Ownership fails at boundaries

Most customer harm happens at the seams:

-

between feature and support,

-

between automation and human fallback,

-

between “working as designed” and “working as expected.”

These handoffs are invisible inside teams and obvious to customers.

When decisions are evaluated through internal lenses—velocity like uptime, ticket volume, and cost, teams rationally optimize their metrics and unintentionally degrade the journey. Each of these decisions makes sense in isolation. The failure appears when the customer gets surprised.

Focusing on the customer journey asks teams to reason end-to-end, even when they don’t share a manager, a roadmap, or incentives.

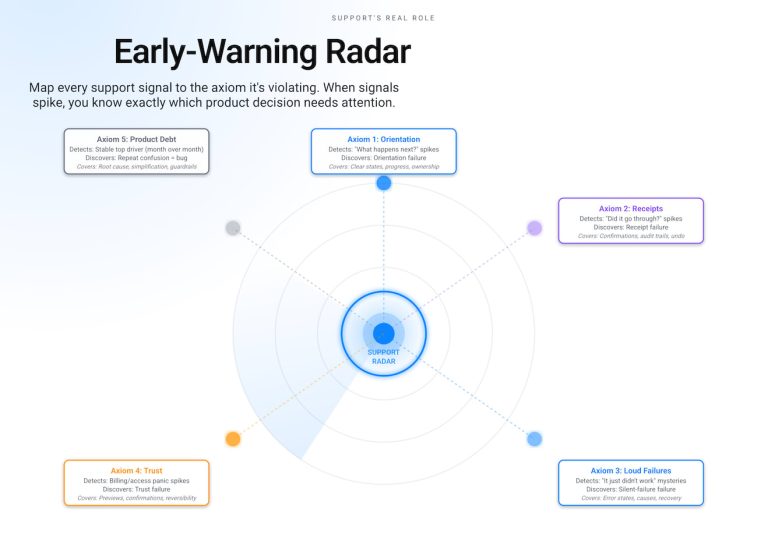

Failure classes are broken customer expectations

Using the customer journey as a frame gives you a clear way to classify failure. You can triage by which customer expectation was violated and carried forward.

For example:

-

When the customer’s mental model breaks (and you see confusion), it doesn’t matter specifically whether it’s an API bug or a UX miss.

-

When customers don’t tell you that they are having problems and your observability system doesn’t see it either, it’s a twin problem.

-

When a reasonable customer mistake keeps happening and becomes an expectation of failure, it might be genuinely hard to reverse.

Once you anchor failure to the journey, debates about ownership become easier. Teams may still disagree on fixes, but they can agree on whether a decision preserves continuity or introduces surprise.

Why cross-training sometimes works

One way to solve this problem is to move people around within internal teams so that they see more (and different) types of problems. The intuition is sound: exposure builds empathy.

But it’s a flawed assumption. Someone who can’t identify root causes in their home team will usually just relabel symptoms elsewhere. They return with anecdotes, not insight.

Cross-training works much better when it forces people to confront the same class of customer harm under different constraints. The value isn’t context switching. It’s judgment calibration.

A product IC who has shipped features, been on-call for multiple teams, and debugged downstream fallout starts to recognize patterns that transcend teams. They don’t ask, “Who owns this?” They ask, “Where does the journey break if we do this?”

That’s not collaboration. That’s shared judgment.

Why rotations need sense-making to matter

If you want cross-training to strengthen ownership rather than dilute it, rotations must be designed around exposure to failure classes, not roles. You need to be able to identify decisions, not just execute tasks. And you bring it together to find results.

Every rotation should end with questions like:

-

Which customer expectations failed repeatedly?

-

Which tradeoffs looked rational locally but harmful globally?

-

Where did the journey rely on assumptions that didn’t hold?

Without that synthesis, experience stays anecdotal.

The customer journey as a tie-breaker

The most practical benefit of journey-anchored thinking is how it resolves disagreement.

When two teams disagree, the deciding question isn’t who owns the fix, whose metric matters more, or who should escalate.

It’s answering this idea:

Which option preserves the customer’s ability to move forward without relearning the system?

Answering this question makes the tradeoffs explicit rather than hiding them. Teams still choose speed over polish, or automation over human review. But they do so knowing where the journey bends and what debt they’re incurring.

That’s a fundamentally different ownership model focused on the customer.

Where teams misuse the customer journey

This approach fails when the journey is treated as a documentation artifact, a CX diagram disconnected from decisions, or a rhetorical shield to block progress.

The journey isn’t a reason to stop shipping.

It’s a way to understand what you’re breaking when you do.

Designing for continuity, not consensus

Ownership problems disappear when teams share a way to evaluate impact that transcends org boundaries.

The customer journey works because it doesn’t belong to any team. It also works because it reflects the system customers actually experience, not the one we wish they did.

When teams don’t share a manager, the customer journey becomes the only system allowed to overrule local optimization. It’s the map to design organizations where good judgment scales without permission.

What’s the takeaway? Ownership problems aren’t about roles; they’re structural. The customer journey is the only system every team touches but no one controls. Make it the tie-breaker.